The Battle of Passchendaele in World War 1 is regarded as a symbol of the futility and devastation of war. Hubert Essame was a distinguished British Army officer who served in both world wars. He questioned why Field Marshal Douglas Haig chose to attack in an area of reclaimed marshland. For two years the Allies knew this ground became a bog when it rained. But still he pushed on with his objective through August and into November 1917.

It had been intended to attack the German line on 25 July 1917 but the French weren’t ready. Finally word came on 30 July that zero hour was confirmed to be at 0350 the next day. Essame describes the beginning of the attack. At 0300 all was quiet following two nights of exceptionally heavy shelling by the Germans. The men had filed out of their dugout to assemble in trenches. Ahead of the trenches were three taped lines. Each line was a target for the troops. They aimed to reach and consolidate them in their attack.

Suddenly at 0350 the sky behind the men and at their flanks erupted. Essame says the blast was so deafening that the troops jammed their fingers in their ears as the ground shook. Each time there was a barrage from behind the men moved forward another twenty-five yards into the gloom.

This is where Private John Govans found himself. He was the younger brother of Henry Govans. Born in 1895, he was the son of Robert and Isabella Govans. Before joining up, he lived in Hurlford, Ayrshire. He belonged to the 6th Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers.

Like many other young men, John probably hadn’t traveled far from his home before war broke out. It is difficult to imagine how he coped in such difficult circumstances as theAllies attempted to capture the ridges around the village of Passchendaele from the German forces.

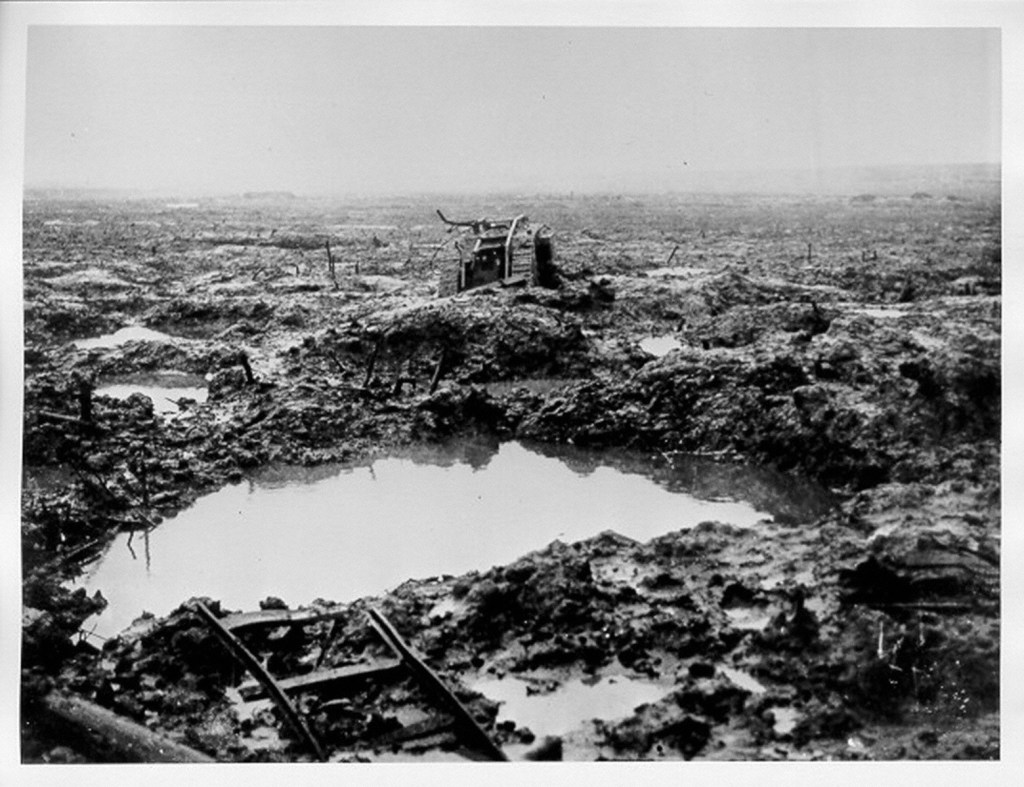

Relentless bombardments devastated the landscape leaving trees as mere stumps. Heavy rainfall continued to churn up mud as troops attempted to move forward. The heavy rain led to many men and horses drowning in the mud. Tanks became bogged down. There was the constant threat of enemy fire and gas attacks. The ceaseless noise of the bombardments was difficult for many men. The mud pulled men in deeper with each step. The dead or injured could not be rescued.

John withstood these horrific circumstances throughout August 1917. Thankfully, after fighting at the front for a few days, battalions were relieved. On 3 August his battalion was ordered to return to camp. Once there, John had time to clean his equipment, getting rid of the mud that covered everything. New tunics were distributed. A Church of Scotland service was held in the field next to HQ at Cameron Camp.

Time away from the front must have come as a great relief. John’s day was filled with physical training, as well as bayonet and musket practice. During their time at camp, promotions would also be made. At some point, John was made a Lance Corporal. On other days there was a Battalion route march followed by games. Baths and showers were allotted in the evening.

On 16 August, a warning was given that they would be on the move the next day to St Lawrence Camp. On 18 August the Battalion had an inspection of battle order. On 19 August the Battalion moved to Hill 16 and camped there.

On 20 August there was shelling overhead which was mostly shrapnel from shells bursting near observation balloons. In the evening of 21 August the Battalion moved to the forward area known as Bill’s Cottage. From that point, the Battalion came under constant artillery fire.

On 22 August the order was received that the battle would continue. The attack would begin at 0700. Intelligence was received from the front reporting huge casualties. Many officers and NCOs had been killed. The situation was extremely difficult. The men were exposed to machine guns and sniper fire. It would be almost impossible to advance without having severe casualties. HQ was informed of the situation. At first, instructions came back to continue forward. Later in the afternoon this order was changed and eventually cancelled and the Battalions were relieved by other troops.

Casualties for the period 22-27 August were huge. Hundreds of thousands of men fell in the next months before the Passchendaele Ridge was taken. The men had suffered beyond reason. Drenched in mud filled craters they had waited for the Germans to attack. Many had guns that were jammed with mud. They took part in hand-to-hand bayonet fighting while standing knee-deep in mud. There was shouting and machine gun fire all around. Visibility was poor.

It was on 22 August 1917 that John Govans lost his life. He is remembered on the Tyne Cot Memorial Plaque. Many of his comrades are also honored there in Passchendaele, Zonnebeke, West Flanders, Belgium. He was twenty-two years old.

His bravery will not be forgotten.

Discover more from Discovering My Family

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.