Researching your family tree can be challenging. I am particularly interested in finding out about my female ancestors. But have you noticed, how much more difficult it is to find out and learn about their lives? Their stories often get lost and forgotten. The strength and forbearance they displayed during their lives can’t easily be seen.

In the nineteenth century, when a woman married, she would traditionally take her husband’s name. There is then no trail to follow using a woman’s birth name. This makes searching for a female ancestor particularly difficult. If a marriage certificate can’t be found, women can vanish without a trace.

Census forms, marriage certificates and death certificates give information about the husband’s occupation. This gives a useful insight into their life and provides areas for further research. Men sometimes have army records that give a wealth of information. Sadly, there isn’t an equivalent for women in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Researching women isn’t impossible, just more difficult. Try to read between the lines of a census or marriage certificate. Look at the number of births and the dates of these births, and sadly the deaths of children. It is easy to see the constant demands of childbirth. Sometimes census forms might show an occupation, so it’s always worth checking the original document.

Catherine Henderson Campbell is a woman I have managed to trace through lots of twists of fate. She was my great grandfather Andrew’s eldest sister. She was ten years older than him, born in Brick Row, Carnock, Fife in 1854. Her father, John Campbell, was an ironstone miner at the Forth Ironworks. Her mother was Margaret Blair, also from Fife.

Between 1856 and 1858, the family made the move from Fife to Ayrshire. They settled at 55, Bensley Square, in the little mining settlement near Fergushill, north of Kilmarnock, Ayrshire. At the time of the 1861 census, Catherine was 7 years old and attending school at nearby Fergushill. Her father worked in the local pit. She had two elder bothers and two younger sisters.

In 1870, Catherine married at age 16 (although the marriage certificate states that she was 18). Her husband, Robert Wilson Mckenzie, was a young man from Edinburgh. They married on 30 December 1870 in Irvine, North Ayrshire. Catherine was so young and her husband-to-be was seven years older, aged 23 years. I wonder what Catherine’s parents were thinking? Were they happy she was marrying? Catherine was 5 months pregnant with their first child. Did her parents even know she was marrying? Had they insisted Robert, the older man, marry her? Perhaps she ran away to marry him. Her younger sister Margaret was a witness at the wedding along with Robert’s brother, James.

Robert was brought up in Edinburgh. His family lived in the heart of the city. They first lived at the Fish Market underneath the North Bridge, where you will find Waverly Station today. His father was a silver plater, a good trade. The family moved to Castlehill, at the top of the Royal Mile next to the castle. Robert had seven sisters and one brother. By 1861, Robert was apprenticed to a coach painter. This was most likely working with horse-drawn carriages.

Robert had arrived in Ayrshire by 1870. He and Catherine met, married, and had a son, John Gordon Mckenzie on 16 May 1871. They first lived at Ogilvy Street in Irvine, Ayrshire.

Their first child was quickly followed by James Mckenzie in 1872. More babies arrived every two years. Margaret Blair Mckenzie in 1874, Alexander Campbell Mckenzie in 1876 and Helen Henderson Mckenzie in 1878. This cycle of births would have continued if tragedy had not struck this young family.

On 11 January 1879, Robert Mckenzie died. This happened only one month after the birth of baby Helen. Catherine was now a widow. She was only twenty-four years old. She had five children between the ages of eight and one month old. What on earth was she going to do?

Robert died from pneumonia and dropsy, a condition that causes swelling, usually in the limbs, which is now called oedema. Pneumonia can cause congestive heart failure which in turn can cause oedema. Pneumonia was one of the top ten causes of death at this time. The situation resulted from several factors. These include damp housing, human waste in streets, and an inadequate diet. Other factors were harsh working conditions, overcrowded living spaces, and the absence of hot water. One word covers all of these – poverty.

Catherine had no time to grieve the loss of her young husband, dead at only 32 years old. She needed a plan. The family had recently moved from Ayrshire to Cowlairs, beside Springburn in Glasgow. In 1866, Cowlairs was the main workshop for the North British Railways Company. Springburn became a global centre for railway-related manufacturing. It was the first place in Britain to build locomotives, carriages and wagons all in the same place. It’s no wonder that Robert got a job there. The family must have been so excited about what they presumed was a secure future. The family were living at 20, Ashvale Row, East Cowlairs, when Robert died.

The next chapter of Catherine’s life was about to start. What would a twenty-four-year-old widow with five children do next? How would they survive? She had given birth to her youngest only a month before.

Catherine gathered herself together and headed to Edinburgh. This was where Robert’s family still lived and worked. Her in-laws must have helped Catherine find nearby accommodation for herself and their grandchildren. What a relief this must have been. By 1881, two years after Robert’s death, Catherine and her young family were living at 16, Jamaica Street in Edinburgh. Her in-laws lived at 10, Jamaica Street.

Catherine had accommodation but she also needed to earn a living. The 1881 census shows she cleaned offices in the city. It is possible that the children’s grandmother or aunts helped with childcare.

Ten years later in 1891, Catherine had moved to 61a Cumberland St, Edinburgh. She was a charwoman. Char work was the most common paid work for widows at this time. Catherine would have worked for an hourly wage and would have a part-time contract. She may have had more than one job. James, 18, Alexander 14, and Helen 12, were still living with her. John, 19, her eldest child, headed to the military, and joined Princess Louise’s Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. Later, he fought in France and survived WW1 with the Royal Scots.

Four years later in 1895, Catherine was forty-one years old. She married for the second time. Robert Carson was a fifty-eight year old Irishman who lived and worked in Edinburgh throughout his adult years. He was a porter when they married. He may have worked in a hotel, a warehouse, or maybe at nearby Waverly Station.

Six years into their marriage in 1901, the census lists the couple living together at 43, George Street in Edinburgh. Helen, the youngest child, is now twenty-two years old and still living with them. Robert, by this time, was a caretaker and Helen a bookfolder.

Being a bookfolder required Helen to fold large sheets of printed paper in the correct sequence as part of the bookbinding process. This would require dexterity and attention to detail. The work was physically demanding and she would stand for many hours doing repetitive tasks. This was a skilled trade.

Sadly, for Catherine, life yet again took another unexpected turn. On 16 July 1901, Robert Carson, her second husband, died of pulmonary congestion and pleurisy. Catherine, aged forty-seven, was a widow again.

At this time, her son, James, moved to Clerkenwell in London, England. He married, had a family of his own and became a printer.

Margaret, her eldest daughter, married a forester and moved to Inverchaolain Estate in the Cowal Peninsula, Argyll.

Alexander, her youngest son, became an apprentice in a printing firm in Edinburgh.

Yet again, Catherine, had to rely on her own means. In 1911 she was still living in Edinburgh at 43, George Street. Helen, her youngest, then thirty-two years old and single, lived with her. Her brother Alex, was thirty-four and single, also lived at home. Catherine found work as a caretaker of offices in the city. Helen stayed at home and ran the household. Perhaps she carried out paid work from the home. Alex was a printer. They lived in an apartment with 2 rooms.

After a long life, Catherine died eighteen years later, aged seventy-six. She was living at 41, Clarence Street, Gorbals, Glasgow and died on 30 January 1929. She had breast cancer. Her death certificate was signed by her son Alex.

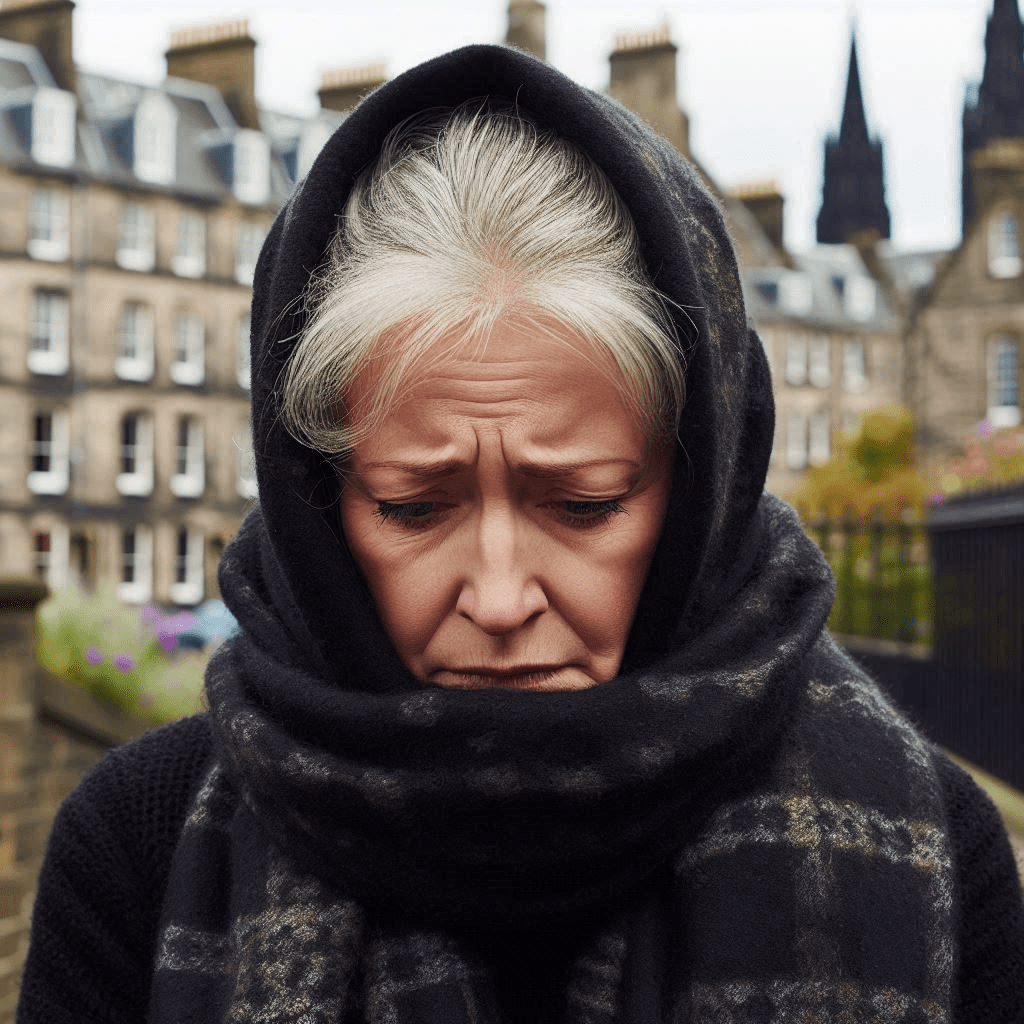

Catherine’s life story followed many different paths. It is one worth telling. She led a remarkable life and her determination shines through. She kept her family together despite all the odds. Remarkably, she lived to see her children become successful. This was most definitely down to her efforts through difficult times. She was a strong woman who found her own way in the world ensuring the survival of her family.

Discover more from Discovering My Family

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

very strong woman, you have reason to be proud

LikeLike