Throwing light on the life of an ancestor can often reveal an experience so different from anything known today. Suffering and poverty were common in the nineteenth century. The life story of my great grand-uncle is shocking, but one that would be shared by so many other miners. His life was indeed one of those tragic discoveries. John Francis Campbell was the eldest child of John Campbell and Margaret Blair. His life story brought into focus the dangers that my ancestors, who were miners, faced daily.

John moved with his family to Benslie, Ayrshire from Fife. He wasn’t sent to school, although his younger brother Alexander, who was ten, did attend the local school at Fergushill.

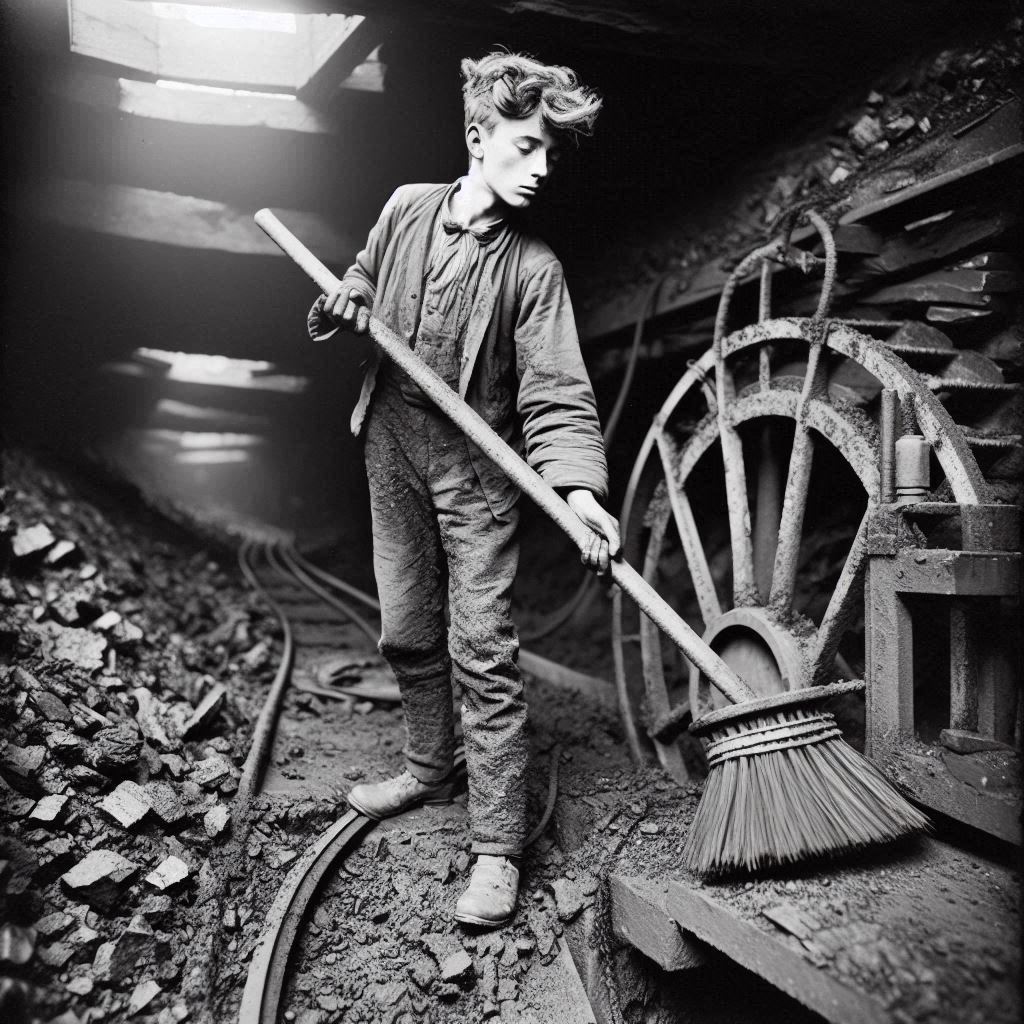

John worked down the pit in 1861. He was a drawer. This was a hard job, tough for an adult never mind a twelve-year-old boy. Each day, John was sent down into the darkness of the pit. He would only have a candle, or if he was lucky, a safety lamp to guide him in his tasks. He would work alongside his father, a hewer. John transported the coal his father extracted from the seam. He pulled and pushed heavy coal tubs from the coal face to the pit-bottom. He moved these tubs along narrow roadways. Working twelve hours at a time, with few breaks, John must have been exhausted. The tubs weighed up to 600kg and the roadways were often only 60-120 cm high.

The physical effort required of a child is jaw-dropping. John’s endurance is humbling. The danger of a cave-in was never far away. John risked respiratory illness through inhaling coal dust. He must have been such a brave and strong boy.

As time passed, John became a coal miner like his father. By 1871, he was a strong twenty-two-year-old man ready to marry a local lass from Stevenston, called Marion Finnie. Their wedding was on 14 July 1871, a rare and happy day for John and the family. Once married, John and Marion had three children:

- Thomas 1873

- John 1875

- Annie 1879

Like many other mining families of that time, no doubt, they would have gone onto have a large family. Twelve or fourteen children was fairly common. But tragedy struck.

John and Marion lived in Sourley, just outside of Irvine. He worked as a brusher in the nearby Fergushill pit. This was a highly important job. John used brushes and brooms to clear away dirt and debris from the mine’s machinery. This would ensure smooth operation of winding engines that lifted coal and men to the surface. He would also clean the steam engines that pumped water out of the pit. Flooding was always a danger for miners. He kept the roadways clear. This action reduced the risk of explosions. Fires could also occur when a certain quantity of coal dust mixed with air. It was a task that required a great deal of responsibility. Working conditions underground were very cramped and dark. John was also involved in repairing roofs and the sides of the pit.

On 14 October 1880, the pit roof where John was working collapsed on top of him, trapping his foot. Unfortunately, John had his foot amputated due to the accident. Undergoing such drastic surgery in 1880 was fraught with dangers. A medical professional would have made an initial assessment of the injury. The decision was made to remove his foot. John would undergo the operation in a makeshift medical facility at the pit. Alternatively, he would have been taken to the hospital for the procedure.

In 1880, chloroform was used as an anaesthetic. This had been widely used since 1850. The surgeon would next clean and sterilise the area to be operated, on as much as possible. Joseph Lister had promoted the importance of sterile surgery using antiseptics from the late 1860s.

The foot was then ready for amputation. A saw was used to cut through the bone. A technique had been developed to preserve the heel pad. This ensured the better fitting of a prosthetic during rehabilitation. Not all patients were given a prosthetic at this time.

The wound was dressed and bandaged and care would be taken in an attempt to prevent infection. To promote healing, John would require bed rest and his leg would be elevated.

Tragically for John, despite the best efforts of his surgeon, Mr Milroy, he died four days after the operation. The cause of death was given as amputation of the foot and inflammation due to pleurisy.

Pleurisy causes a sharp chest pain that John would feel every time he moved or breathed. John would have inhaled a lot of coal dust on a daily basis. Many miners developed pleurisy and they were prone to infections. The physical strain of their work weakened the immune system. Accidents like John’s led to infections. Open wounds often became infected. There was also a lack of quick and good medical care. Even minor injuries become infected and lead to sepsis. Tragically, John Francis Campbell died at the age of only thirty-three years on 18 October 1880 at 5.50pm.

It’s impossible to know what standard of medical treatment and surgery John received in 1880. He may have suffered blood loss, shock, gangrene, fever, or sepsis. Given that John was also suffering from pleurisy, the odds of survival were stacked against him.

His death must have been a terrible shock to his young wife, Marion. She was only twenty-nine years old when her husband died. She had three young children who needed her care. She was also three months pregnant with their fourth child.

On 29 June 1883, Marion married for a second time. Gilbert Muir was also a miner and they had three children together. Marion died in 1920 in Benslie, Ayrshire.

This has been a sad but common story of mining life in Scotland in the nineteenth century. Many men lost their lives in pit accidents and many women were left widows. John worked down the pit for almost twenty years. He gave up his life while contributing to coal production for the industrial revolution.

Discover more from Discovering My Family

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.